November 15, 1925 – August 20, 2021

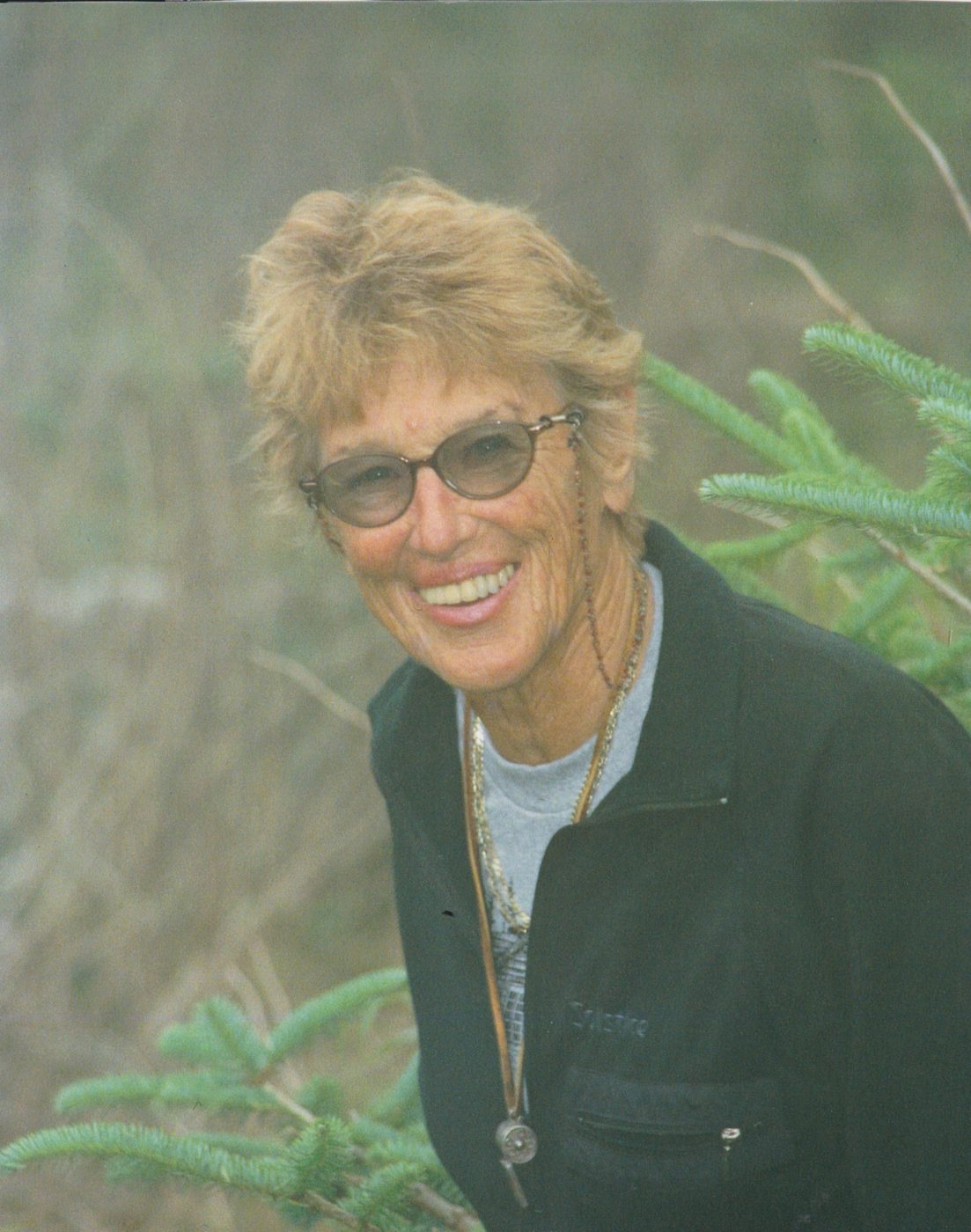

Anne Springs Close, a noted conservationist, philanthropist and the last living person to have flown across the Atlantic aboard the German airship Hindenburg, died on Friday, August 20th Fort Mill, SC, in her home of 72 years, surrounded by her children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. The cause of death was injuries from a falling tree.

She was 95.

Mrs. Close, called “Baggs” by her family and friends, was born in Charlotte on November 15, 1925, to Elliott White Springs and Frances Ley Springs of Fort Mill, South Carolina.

Elliott Springs was a highly decorated aviator in World War I, credited with 11 kills. He claimed 12. His memoir Warbirds was a best-seller and launched him on a career as a successful writer in New York until he returned home in 1931 to take over the family cotton mill business from his ailing father.

He met his future wife Frances, of Springfield, Massachusetts, aboard an ocean liner during an Atlantic crossing. Her family’s construction business built two of New York City’s famous landmarks, the Flatiron building and the Chrysler building.

Anne’s brother Leroy, called “Sonny,” served in World War II in the Army Air Corps. He was killed on Mother’s Day 1946 in a flying accident. That tragedy left Anne the sole heir to her father’s considerable fortune.

Anne Springs attended public school in Fort Mill and continued her education at Ashley Hall in Charleston and Chatham Hall, graduating in 1943. She attended Smith College, where she studied physics.

On V-E Day (Victory in Europe, May 8, 1945), she and classmates traveled to New York City from Northampton to join in the celebrations. Some friends showed up “under the clock at the Biltmore Hotel” – a well-known meeting place–with several U.S. Navy officers in tow. Their aircraft carrier had been badly damaged by Japanese planes and was in the Brooklyn Navy Yard being repaired.

“My friend said, ‘Just pick one,’ Mrs. Close recalled in an interview, “So I said, ‘I’ll take him’.” She and “him” – Lieutenant Hugh William Close, of Lansdowne, Pennsylvania – married a year later.

His ship, the U.S.S. Franklin, was one of the most continually attacked vessels in the Pacific war. In one engagement, Lt. Close reported to his muster station and was told to return to his cabin and put on shoes. While he was doing that, a kamikaze plane flew into the muster station, killing everyone.

The newlyweds lived for a time in Port Chester, NY. In 1947, when Anne became pregnant with the first of their eight children, they moved to Fort Mill. Bill eventually took over the family business, which now included not only the mills but also a bank, railroad, newspaper and insurance company. He died in 1983.

Late in her life, Anne noted that she had lived in the same house for 72 years, “and just a hundred yards from the house I grew up in.” She added with a laugh that she had even once been named “Fort Mill Man of the Year.”

She is more likely to be remembered, in Fort Mill and beyond, as the founder and creator of the Anne Springs Close Greenway, the 2,100-acre nature conservancy in Fort Mill. In the 1980’s, concerned by the encroaching urban sprawl of Charlotte, she reached out to Patrick Noonan, founder of The Nature Conservancy, and to Chuck Flink, a leading planner of greenways. Together and with others, they developed a far-sighted land-use plan, placing 2,100 acres of family-owned land in a conservancy, while retaining 4,000 acres for development. Two prospering local communities, Baxter and Kingsley, are the result of that planning.

“That’s one of the things we’ve been cited for,” Mrs. Close recalled, “Most developers build first, and if there’s anything left over, they would make a green space. We did it the other way around. We made the green space first.”

She added that “it took several years to get that done. We signed all the legal papers by candlelight because it was three weeks after [Hurricane] Hugo and we didn’t have electricity. And by this time, the greenway was brown. It was a disaster area. Hugo went right over it. So, it took five years to get it ready to open. We opened in 1995, on Earth Day.”

Mrs. Close remarked that the COVID pandemic has significantly increased membership in the Greenway.

“We’ve doubled our membership in the last year. People go there to get outside. It’s been a great success.” Reflecting on the “Anne Springs Close Greenway” signs, she added with amusement, “People think I married Mr. Greenway.”

When the last of her eight children left home for college, Mrs. Close was appointed to the board of Wofford College, in Spartanburg, SC.

“I was the first woman board member,” she remembered, “and I ended up being the chair for a couple of years. And I loved that. Then I went on the board of the National Recreation Association, which is a big board, 65 people. I was scared to death, but I did it, and I became chairman. We’d meet twice a year, in all sorts of countries. That was a wonderful experience. I did it for 15 yrs. Then I was five years on its foundation and met a lot of interesting and fun people. I’d been going to textile meetings, which is boring as hell. And I got a couple of national awards, which were nice.”

Mrs. Close imbibed her sense of community spirit and “giving back” from her father, Elliott Springs, who owned seven cotton mills in four towns.

“He did a lot of things for people in the mills,” she recalled. “He was the first to have a cafeteria in the mills so that people could have a hot meal. He had a medical department and recreation programs in every town. He built a golf course. The other mill owners told him that lintheads would never play golf. ‘Lintheads’ is what they called people who worked in the mills. They told him, ‘You’re wasting your time.’ He said, ‘Nevertheless,’ and built it and they did play golf. You could get a membership for $4 a week. And he built Springmaid Beach, a resort in Myrtle Beach, that had almost a mile of oceanfront, where mill workers could go and stay for a dollar per person per night.”

Mrs. Close may also have inherited her sense of adventure from her father. In 1936, he cabled her mother permission to return to the U.S. from Europe aboard the Hindenburg, on the grounds that it was “perfectly safe.”

Anne was ten years old. On boarding, her mother was presented with a plaque honoring her as the 1,000th passenger to fly aboard the airborne leviathan.

“They gave her a ‘Heil Hitler,’ but we did not ‘Heil’ back.”

In 2017, on the 80th anniversary of the day the Hindenburg proved somewhat less than “perfectly safe,” Mrs. Close was herself given a plaque by the Navy Lakehurst (N.J.) Historical Society.

Over the course of her crowded life, “Baggs” traveled to more than 60 countries, including Swaziland, Bhutan, Mongolia, Iran, Mali and Yemen, which she nominated as “probably the most exotic.” Every summer, she took her population-exploding brood of grandchildren and great-grandchildren to Switzerland on hiking trips; as well as on horse pack trips on Sheep Mountain in Washington State, which she called “My favorite place in the world.”

She went to Africa many times. “Out in the bush, it’s just magical,” she said. In addition to her Hindenburg distinction, she may be the only octogenarian to climb Mount Kilimanjaro three times. But her most challenging ascent, she said, was New Hampshire’s Mt. Washington, when she was 88. “That was crazy,” she recalled. “That was insane. That killed me.”

Mrs. Close was diagnosed with macular degeneration when she was 55 but was able to continue to drive until age 81. But blindness, for her, proved merely a nuisance, rather than a handicap, as her late-life mountaineering attests. She continued to go on bicycle trips and horse pack trips. At 92, she made her final pack trip with her “hero,” Claude Miller, and her “other children,” Daniel Knox and Mary Gin Barron.

A tragedy struck in 2014 while hiking in Adelboden, Switzerland with her great family friend, Susan McCrae, and others. Susan suddenly died of a heart attack, leaving Mrs. Close alone on the mountain. But using her time-honed instincts, she was able to feel her way down the mountain and convey what had happened, using her rusty, but serviceable German language skills, taught her by her beloved governess, Marie “Toto” Dehler.

“Nothing stopped her,” said her physician daughter Katherine “Katy” Close.

She continued to travel up to the end, visiting her far-flung family in the Bahamas and Guatemala. She visited grandchildren and great-grandchildren from New Orleans and Nashville, Seattle and California.

She and her son “Buck” made a number of visits to Haiti, where she supported a group of nuns who called her affectionately “La Reine”—the Queen.

Blindness proved no impediment to her reading. She and her trusted companion, Kenny Walker, spent countless hours listening to audiobooks while driving thousands of miles. She did the New York Sunday crossword as recently as last week aided by her children and in-laws.

Between her indomitable spirit, her sense of humor and a fatalism born of deep religious faith, the irony of being felled by a branch while sitting on a bench outside her home of 95 years was not lost on her. At the hospital, she remarked with characteristic wryness, “I saved one too many trees.”

She was predeceased by her husband, Bill Close, her brother Sonny Springs and her daughter, Monnie McKee Reed.

She is survived by her eight children: Crandall Close Bowles, of Charlotte, NC; Frances Allison Close, of Columbia, SC; Leroy Springs Close, of New Orleans, LA; Patricia Grace Close, of Leavenworth, WA; Elliott Springs Close, of Fort Mill, SC; Hugh William Close, of Fort Mill, SC; Derick Springsteen Close, of Charlotte, NC; and Katherine Anne Close, of Pawley’s Island, SC; 28 grandchildren and 24.5 great-grandchildren.